Keystones, Negotiations, Relationships and NetGain

My young colleague and I were talking about why it’s so hard and so important to craft fair, wise, and enduring solutions for our clients. I likened the objective to the carving of a keystone, alluding to something so ancient she didn’t know what I was talking about. So she asked me to explain it to her and was so impressed with its metaphorical usefulness that she suggested I try to write about it.

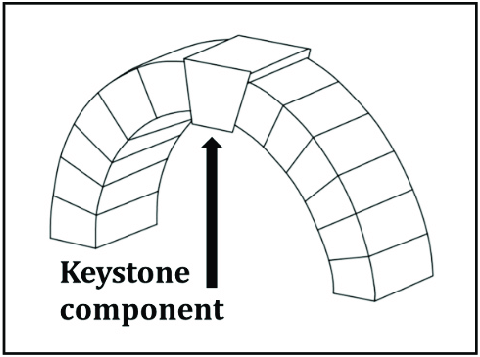

A keystone is the last chunk of stone that gets dropped into place at the top of a stone arch. It is precisely shaped to lock the rest of the structure in place. The analogies, similes, and metaphors suggest themselves, don’t they?

Or they would if the current generation absorbed every arcane crumb of knowledge accumulated by their parents, grandparents, and great grandparents, back until the beginning of time.

The principle behind the keystone can be traced to the masons hired by King Solomon to build his first temple, around the 10th century B.C., though in practice it was in use less perfectly before that. It’s that old. Centuries later keystone construction skills became a prerequisite of membership for the Order of Mark Masons, a sort of elite fraternity of Freemasons. Not surprisingly, given the global reach of Freemasonry and the practical value of skilled stoneworkers, building techniques continued to rely on some of these principles from the Middle Ages when masons guilds first formed, through to the 19th century when iron and steel framing, and reinforced concrete, reduced reliance on the clever stacking of stones to build great structures.

Building features that were common a few generations ago are relatively rare now, seldom noticed, and even less frequently explained. Still, the metaphorical value of the keystone made enough sense to my 20-something colleague to be worth reviving because it helps understand why long term relationships last or perish and how, like the Mark Mason, NetGain strives to craft the snug fitting stone that locks these opposed elements into a mutually reinforcing structure.

Think of a relationship between a charitable nonprofit corporation and a commercial enterprise and form of relationship they negotiate for mutual benefit. It might involve a complex real estate development or something as simple as corporate sponsorship of a charitable event or program. In order for this relationship to last, it must meet both parties’ needs and expectations.

If the charitable organization’s interests are represented by one stack of stones, and standing apart from that are the stacked interests of the business, some means must be found to arch the stacks towards each other so they can meet in the middle. It has to have symmetry or the structure will heave to the side and buckle. In the relationship between commerce and charity, this would be analogous to the quality of fairness in which both parties recognize enough reciprocal value to justify the concessions each must make.

Imagine negotiating terms unlike organizations that are actually opposed to one another on some matters, succeeding in achieving the perception of fairness, but requiring a handy means of locking all the terms in place before any of them fall back into doubt or dispute. That would be like trying to support all the stones in the archway overhead and keeping them in place for as long as, say, Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.

Footnote to history: his temple was destroyed by the Babylonians. But aren’t the arched gates amazing?

Without the keystone, these structures would never stand, or if artfully mortared in place, would soon crack, shift, and rain stones down on the heads of pilgrims passing beneath. Then the two stone stacks forming the sides would fall inwards in a pile of rubble along with the walls they were supporting. Descriptions of collapsed relationships sometimes employ similar language.

Like most structural failures, the overarching agreement in a relationship will fail if it isn’t designed to bear the weight of the two parties leaning in on it. The magic of the keystone is that it uses that weight to hold all the pieces in place; the two joined stacks and the archway that connects them. Their weight holds the keystone in place and its shape transmits the opposed forces in directions that stabilize the whole.

If the keystone is too small, its angles are incorrect, it’s made of weak material, or it isn’t positioned precisely, it’s not going to be strong and durable. Like Jericho, the walls will come tumbling down.

Incidentally, here’s a Bronze Age stone gate restored in an actual wall of Jericho.

Of course it had to be restored because, according to the testament, it fell down while the Israelites circled it looking for a way through fortifications deemed to be impenetrable. Note the huge, flat stone lintel spanning the two upright columns and imagine how much more difficult it would have been to hoist each of these giant, one-piece structural elements into place, and how much less stable the structure would have been than one built of cut stones, carefully engineered to transmit weight outwards to the abutments and downwards to the footings. Although there’s nothing wrong with lintel construction like this, more sophisticated engineering was required for taller and more elaborate structures.

It's tempting to compare the kinds of curved, lofty overhead structures made possible with keystone construction, and draw analogies to negotiation of deals between organizations and people. But that isn’t the focus of this analogy.

It’s the apparent suspension of heavy things over time, made possible by assembling the piece in such a way that the two inward leaning stacks add force to the element that locks them together, making them stronger, separately and together. The keystone isn’t balanced on top of the stacks, precariously swaying if they shift to or fro. It is intentionally designed so that their weight bears on the keystone. The more support they draw from the structure, the more firmly the pieces are locked in place.

This is what enduring agreements require. Circumstances will change, but as long as both parties are drawing strength from the agreement, it will remain in place. This is the true strength of an agreement, whether a contract or any other formalized relationship. Although we admire people who are bound by their words, words are not what keep contracts in place. Courtrooms are full of people in disagreement over agreements. Half of avowed matrimonial unions end this way, and corporate agreements fail at comparable rates (adjusted for duration -marriages intended to last much longer than the average corporate contract). If it’s going to hold up, for it to be more than words, the agreement must function to the benefit of both parties in a balanced, symmetrical way.

There’s no need to belabour the finer points of the analogy, but it’s worth drawing out the implications for NetGain’s approach to deal structuring.

First, neither party succeeds if the other fails, so negotiators must concern themselves as much with the other party’s success as with their own. Second, the benefits anticipated early in the deal’s term should be expected to grow over time, increasing the deal’s value so that both parties tend to the relationship, reinforcing it when necessary.

In practical terms, this imposes conscious reciprocity on the deal at the time of conception and negotiation. Our culture prefers to treat negotiation as a zero-sum game in which there is a fixed amount of value to be divided according to power imbalances or strategy. That’s like building one side of your gate taller than the other and being disappointed when it keeps falling over. It’s as primitive a form of negotiation as a pair of fishmongers haggling over the price of a day-old mackerel. It’s no way to start a long term relationship.

What’s required in our experience is non-adversarial bargaining. Both sides must be cognizant of the degree to which the other might benefit from terms of the deal. The more value they can build in for the other side, the more they can seek to extract from the terms favouring them, A lopsided agreement will not prove to be a victory. Vanquishing your counterpart in negotiations will not make them better motivated and able to honour the terms of agreement. Yet this is the unsophisticated way we think and talk about negotiations in all aspects of our lives. We celebrate getting something for nothing, for having finessed or coerced someone into something so beneficial to you that it’s hardly worth anything to them. This is too often the objective.

Maybe this is suitable for quick transactional agreements, like buying and selling commodities at the spot price and shaving a few points off the global price, but like fish-market haggling, those aren’t the deals that make a difference in the long term.