Ventures in regenerative farming and circular economy on Toronto’s doorstep

Hopetowns Community Ventures and the commercial/charitable widget

When economic sectors collide you get unintended but predictable consequences. In consultant’s parlance, results are often suboptimal and rarely predictable.

Their motives are contradictory. Government is concerned more with accountability than profitability. Businesses care more about profit than the public interest, and because time is money, they strain against the ponderous processes of public sector partners. If a charity gets caught up in their deal, like a minnow among whales, they’re lucky to survive.

Everyone can think of a private-public partnership (a 3-P) gone wrong. But in Port Hope, NetGain got a chance to steer one in the right direction.

The eminent architect, Phil Goldsmith, invited us to meet with the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario about a property they considered acquiring. It was a 150-year old structure on Port Hope’s main street that had been occupied by the Royal Bank of Canada for at least a century.

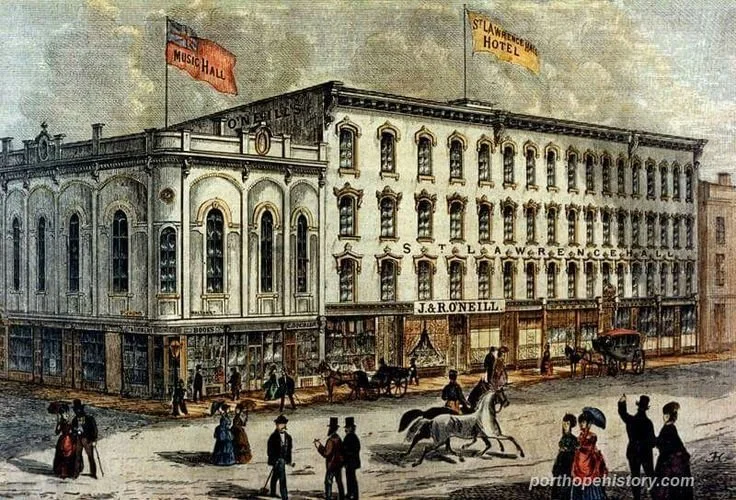

Historical drawing of the St Lawrence Hotel and the Music Hall, later to be known as the Opera House, at its opening in 1871

The Bank wanted to give it away for $1. The question was whether or not they should, whether or not the community could make good use of it and, if so, whether the ACO should adopt the building before the Bank changed its mind and put the building up for sale.

It was once a landmark structure, familiar to all who lived there. What made it remarkable was the concert hall on the second floor. In 1871 when it opened, 600 people attended a performance of a female operatic soloist, accompanied by a grand piano by lamplight. When changes to the fire code caused it to be closed to the public, it had gone from being a vaudeville hall to a small theatre to a cinema, and in its final days, a gymnasium. In fact there is still a badminton bird stuck in a brass ceiling fixture 25 feet in the air, and the painted lines of the court are still faintly visible under the grimy floor lacquer.

The catch – and there’s always a catch – was that adaptive reuse of the “free” heritage building would cost millions of dollars. This $1 asset was actually at least a minus-$4,999,999 liabiity.

The building looked intact, if somewhat degraded by bad renovations. The ornate masonry had been buried under a thick layer of fake-stucco. Canopied shop windows and glass doors had been enclosed as bank office and service space, with smaller windows and fake wood trim. Drop tiled ceilings had lowered the headroom on the ground floor by about three feet, and the open retail space had been sectioned into little offices and utility rooms behind the tellers’ counter.

Worst of all was the desecration of the long-shuttered, second floor music hall. Although its 20-foot high, arched windows signalled outwardly that all was well, its insides had been carved up to accommodate modernization of the bank’s HVAC system. Rather than putting this equipment on the rooftop, it had been expedient to mount it inside the music hall and to chop out channels in the pine flooring to install ductwork. Even the ceiling had been cut open to permit reinforcement of the joists, which remained exposed behind gaping holes. This, like the HVAC installation, could have been accomplished from the exterior to preserve the hand-laid wood interior, but that would have been more complicated and expensive.

In addition to the careless treatment of heritage features, there was still the fire code problem to be addressed. Nineteenth century regulations were much more permissive than 21st century building codes with regard to fire egress, materials, sprinklers, and alarms. Keep in mind that this was a gas lit, tinder-dry structure made entirely of resinous softwood, from which hundreds of people would need to evacuate by a single staircase and exit in the minutes it would take for a fire to consume the whole room. Such waste of human life tends to be discouraged in 21st century building codes, but in 1871, people must have been more nimble. Or less flammable.

The great dilemma, for the Bank, the ACO, the Town’s Mayor, local heritage advocates, and possible recipients of this $1 gift, arose when the building’s condition was weighed against its historical importance. This is where the cross-sectoral perspectives diverged and the building’s preservation was in doubt.

The commercial instincts of the Bank made it preferable that the building be given to the community as a public relations gesture. However there was no organization in town with the resources to repair the damage inflicted on the building by the Bank, nor to operate it sustainably once restored.

Port Hope’s population was only 13,000 when everyone’s home, so it could barely support its atmospheric theatre, the Capitol, and nearby Cobourg was likewise pressed to keep its concert and theatre venue, Victoria Hall, out of financial trouble. Despite the area’s charms, tourists weren’t visiting in significant numbers, despite being 60-90 minutes by road or rail from the country’s biggest city. Overnight stays for arts programming, the lifeblood of festivals like Stratford and Shaw, were unlikely in a town that had fewer than 100 hotel rooms and few restaurants open in the evening.

NetGain rapidly reached a few key conclusions: The building’s restoration and future use couldn’t be dependent on local resources. Toronto would have to be the project’s source for money, talent, and future audiences. Nor could it succeed as a standalone project, because outside resources couldn’t be secured in a town that couldn’t accommodate visitors in sufficient numbers to justify operating the restored structure.

The Architectural Conservancy accepted this general premise and asked NetGain to find a Toronto impresario who might lead the redevelopment project, take title, and operate the building.

This is where the story becomes really interesting. It’s impossible not to go off on a small tangent about why just such an impresario was available at precisely the time leadership was needed.

Albert Schulz’s unhappy departure from Toronto is chronicled incompletely by the media at the time (The dramatic fall of Albert Schultz - Toronto Life ), and doesn’t need to be revisited here except to explain the improbable outcome from a Port Hope perspectives. Schulz, one of Canada’s most accomplished actors, directors, producers, and founder of Soulpepper Theatre, grew up in Port Hope, where his family had roots going back to the 19th century. In fact his father, Peter, who had died when Albert was a child, is still commemorated by a plaque on Walton Street and a nearby conservation area (Peter’s Woods) because so much of the Town’s preserved heritage was due to his effort.

So, when it seemed that Toronto had dispensed with Schulz in 2019, Port Hope received him back with a balance of enthusiasm and skepticism . NetGain advised a general meeting of the ACO that his complicated public profile might make the project more challenging, and all endorsed him as a prospect to lead the music hall restoration.

But, as has already been established, the music hall couldn’t be restored and operated successfully with outside investment, talent, and audiences, without also addressing the region’s tourism deficits. On both the music hall study and prior work on adaptive reuse of the Port Hope pier, NetGain had drawn focus to abysmal visitation and revenue levels relative to competing counties in southern Ontario and relative to Port Hope’s underdeveloped tourism assets.

In other words, the music hall could not stand alone, and in fact didn’t need to. Port Hope is a place frozen in time since the pre-railway and highway days when its port and pier made it a thriving link between the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the inland waterways along which Upper Canada’s great natural wealth was being exploited. For as long as ships under canvas were moving more freight than trains and trucks, Port Hope was prosperous, and later when trains and trucks bypassed the Town, embedded wealth remained preserved, thanks in large part to the Schultz family’s leadership.

What remains are the best 19th-century streetscapes in North America along with an inventory of extraordinarily well preserved century homes. Public buildings like the once-burnt, twice-built City Hall remain very close to their original condition. Nowhere in the business district will you find a chain restaurant or retail store. It has a picturesque river running under old bridges right through the centre of down, down under a high railway overpass to the port and pier, beyond which the blue green water of Lake Ontario stretches out to the horizon. In the alleyway behind the 1871 music hall is an 1817 brewery, once operated by a retired war hero who fought with Nelson at Trafalgar before being commissioned to spank the Americans in the war of 1812 and building the fabulous Port Hope estate called Penryn Park, in which – wait for it – Albert Schultz was born.

This would seem like a small world story, but Schultz and NetGain couldn’t afford to think small about how to leverage the Town’s heritage assets to support the restoration and reactivation of dormant buildings like the music hall. To help Port Hope live up to its potential, Schultz came to NetGain’s office with a mad, feverish, but utterly coherent rationale for refocusing the project on regenerative farming. After bit of eye-rolling and head-scratching, the power of his thinking became evident to us and we set about trying to create an organization capable marshalling the necessary resources and mobilizing people to achieve the objectives of the now incorporated and charitable HopeTowns Community Ventures, and its commercial counterpart Cloverlark Ltd.

Wait, I hear you asking, is the objective to restore the music hall or to promote regenerative farming? In Schultz’s conception, both are elements of a larger scheme to reconnect the Town to its splendid agricultural and natural surrounds, creating a branded tourism experience that optimizes its unique appeal, and in the process fires up a badly needed ecological and economic revival.

That branded experience includes culinary and cultural offerings to be showcased in the restored music hall and elsewhere. So not only did HopeTowns take over the music hall that the ACO had acquired from the bank, it also acquired 70 magnificent acres of shoreline, woodlots, and farm acreage walking distance from the downtown on the west edge of Port Hope, and entered into a funded agreement with the Nature Conservancy of Canada to work jointly to convert 5,000 acres of farmland to regenerative farming. And that was just the start… the full plan creates a circular economy in which farmers who make the switch to regenerative methods will have HopeTowns and Cloverlark buying their premium product for promotion in its showcase establishments downtown, near the music hall. HopeTowns/Cloverlark already has two popular food venues operating downtown, supplied by select local farmers. Its own lakeshore acreage is now certifiable as organic and regenerative land, and has been rezoned for the placement of ecolodge accommodations, alongside three existing cabins, for rental. Roughly a half million dollars have gone into stabilization and preconstruction preparations for the music hall, with the main work dependent on detailed planning and financing.

Again, this is just the start. HopeTowns and Cloverlark are themselves just the kernel of a larger idea, which is to replicate the ecologically and economically transformative effects of this initiative in other communities across the country.

This breathtakingly ambitious confluence of commercial, charitable, and public sector interests is a curiously ordinary NetGain story. First, far predating the pandemic shift to remote work, Canadian banks had reassessed their real estate porfolios and concluded that they should sell off most of their branches, leasing back only what they foresaw needing in the future. It was this process that made the century-old Royal Bank branch expendable at the corner of Walton and John Streets in Port Hope.

Ancient history with Phil Goldsmith on surprise successes on the Neufeld gallery project in Waterloo,, and the Assembly Hall in the former City of Etobicoke, qualified us to raise uncomfortable options for the Port Hope pier many years later. After losing that tussle with Cameco and Town Council, we were the leading candidates to solve the Royal Bank/Music Hall puzzle for the Port Hope ACO.

On the strength of that analysis, it was agreed that outside talent, investment, and audiences were required, which led us to Albert Schultz, who just happened to be ending a career in Toronto and returning to his birthplace in Port Hope, where the ACO was happy to transfer title to the music hall over to him.

This focused his prodigious energy on creative and practical solutions to the challenge presented in NetGain’s music hall study, leading to years of collaboration with NetGain. We helped in the articulation of his vision, with incorporation of HopeTowns and Cloverlark, strategic and business planning, and a succession of unexpected issues arising from this work. It’s too much to describe with great specificity, but NetGain’s help was also sought on political and government relations, cultivation of prospective supporters and advisors, and land use master planning. We’re on hiatus now while Hopetowns consolidates its early gains and musters forces for its next push, but we expect to be drawn back into the next phase of Port Hope’s revival.

Bringing this back full circle to the opening remark about cross sectoral collisions, there are typically three possible outcomes. Fairy-tale public private partnerships are always intended, like Rumpelstiltskin, to spin straw into gold. More often they stall out because none of the players can safely navigate through the conflicting interests of the other parties, resulting in little or nothing. Then, there is what we call “the reverse Midas touch” effect, in which all the most optimistic outcomes seem readily attainable, but the habits of one sector prove intolerable to the others, and the relationships become so toxic, they can turn gold into rat shit.

No one is pretending that NetGain has King Midas’ golden touch, but long experience with the conflicting interests and intolerable habits of all three sectors enabled us to guide RBC and ACO in the preservation of an important asset, and to use that asset to bring leadership and investment to an initiative that appeared at various stages to be nothing but a fairy tale, destined to end badly.