Urban Green Value

This highlights the challenges and shortcomings in how public land management agencies balance development and conservation. It argues that, unlike in the past when land seemed abundant and nature was viewed as a hindrance, today's urban planning must recognize the essential value of green spaces for human well-being and environmental health.

It critiques current asset management practices, which primarily focus on quantifiable benefits of developed land while neglecting the unmeasured value of preserved natural areas. This imbalance often leads to decisions that favour development, even when the long-term benefits of conservation are significant.

It advocates for a more holistic approach to valuing green spaces, suggesting that methods like Parks Canada's ecological integrity framework could provide a way to quantify the value of natural assets. Ultimately, it calls for a shift in perspective to prioritize the preservation of urban green spaces, recognizing their critical role in maintaining ecological health and enhancing quality of life.

Every agency that manages public land, at every level of government across the country, faces a careful balancing act. They must decide, site by site, which land should be developed and which should be conserved in a natural state.

In the early days of Canada, this was straightforward. Nature was seen as an enemy, wilderness marked the frontier, and land was often given away with the promise of "improvement." The sooner trees could be cleared for pastures or buildings, the better.

Today, however, determining where to build is no longer easy or obvious. No one is creating new land, especially green spaces in large cities. The global pandemic made it clear that nature is not the enemy; access to green space is essential for human well-being. We need trees to keep the air breathable, and their shade helps protect us from overheating and skin cancer.

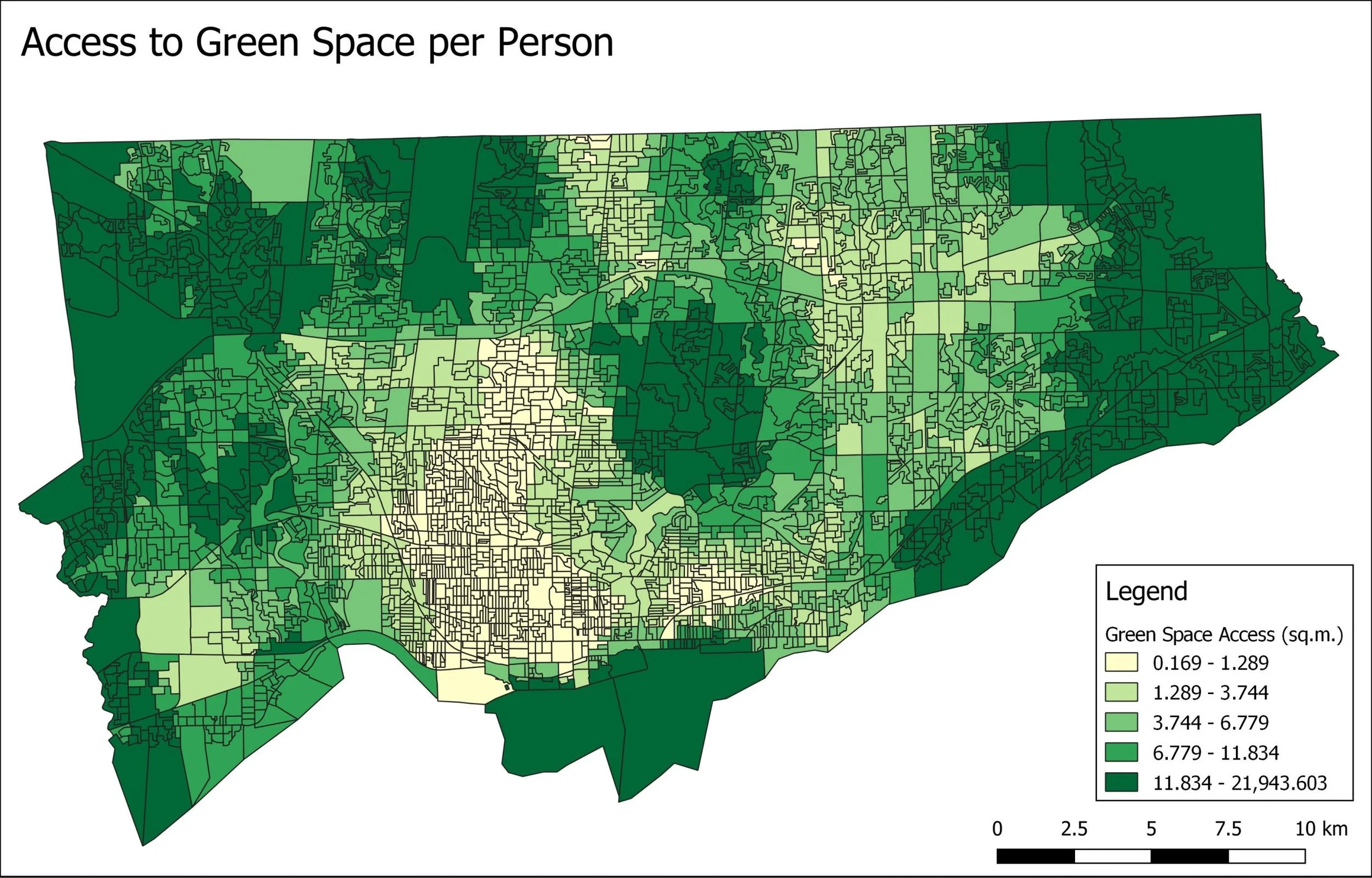

A map of Torontonians' access to green space (Source: Spacing)

Our outdated asset management methods don’t make these decisions any easier. Municipal park departments in Canada struggle to quantify the value of preserved green spaces relative to the value of developed land.

This is a real issue. They have plenty of asset management data for planning and budgeting and know the capital and operating values of facilities and infrastructure according to cost, age, and condition. In contrast, unimproved land with trees, meadows, ravines, rivers, wetlands, and trails—may have theoretical or sentimental value, but have no dollar value except as a potential development site.

Using these systems and methods it’s much easier to justify a parking lot than a tree lot. We know the cost of paving, snow plowing, ticketing, towing, and the annual revenue potential, as well as estimated utilization rates and the benefits of making the park more accessible to drivers.

The opposite case is much more difficult to quantify, and hence less persuasive. If a parks department proposed tearing up the same parking lot to plant trees, there is no inductive data available to make the case. There might be perfectly valid deductions to be made from the general environmental benefits to specific arguments about a particular site, but this isn’t as compelling to publicly accountable decision makers as hard numbers about real costs and benefits..

Intuitively, we know that we shouldn’t build over all our parklands. Yet, bit by bit, we continue to build. Without a balanced method for evaluating preserved green space against facility and infrastructure “improvements,” we make compromises that sound clever but don’t truly serve the public interest.

It's often an either-or proposition because every piece of real estate in a public park portfolio must eventually be designated one or the other; natural/renaturalized land or a building site of some kind. Ecosystems are delicate and mixed-use compromises don’t often meet their environmental goals.

For all of these reasons, land use development plans face predictable opposition. Rationales are incoherent when pros and cons are evidenced differently. There are numerous examples, such as the reversal of housing development on Ontario's Green Belt after the attempt to carve out new building sites for the Premier’s supporters. The fierce controversy about cutting down trees on Toronto’s waterfront for development of a private spa illustrates the same case.

Clear-cut trees at Ontario Place (Source: BlogTo)

Everyone knows the value of housing, but what’s the real cost of ecosystem damage in a sensitive area? Likewise, how do you balance the economic benefits of spa construction and long term employment against the loss of mature trees in a lakeshore park? In neither situation was the loss of green space calculated in terms comparable to the estimated value of the proposed developments.

Without a balanced approach to public land decisions, we tend to approve choices backed by data more readily than options for which costs and benefits aren’t quantified. Returning to the first example, the value of a parking lot is more tangible than that of a tree lot. One has a known value, whether great or small, while the other registers uncertain or null value in our asset management systems.

Without bringing religion into the discussion, there’s something illogical about systems that assume nature can be improved by human actions. Although this is an ecologically false premise, it’s strange that we must always make a case for the value of conserved land whenever a new use is proposed. Yet this is the reality we face. Current green asset valuation methods cannot compete with the quantitative measures used for built assets.

If you’re skeptical, consider a common scenario in municipal park departments. Cities mandate their parks departments to look after both recreational facilities and green space. However, when community centers, rinks, pools, and sports fields are built on land that could otherwise be passive parks or conservation areas, these agencies are faced with inescapable dilemmas.

Lacking the tools to coherently calculate ecological impacts relative to other public interests arising from building projects, land use decisions devolve into contests between calculated benefits and incalculable harm. Although this favours building over conserving, it also tends to paralyze decision-makers. Even the most benign building projects will encounter opposition and delay as advocates from both sides battle it out and elected officials duck for cover. This rarely leads to the best decision for either side.

Parks Canada developed a useful approach to address this issue. They created an ecological integrity framework to assess park conditions and the measurable impacts of development on the long-term viability of natural systems. For about 35 years every national park has been tracking key indicators, from apex species populations to soil, water, and air quality. This data set and monitoring system allows the agency to present credible arguments for changes made to increase or restrict access to fragile environments, to add or removes services and amenities, and to make strategic additions to the portfolio as a whole. Infrastructure projects are routinely proposed, evaluated, planned and completed, all backed by defensible rationales that consider the value and condition of land in its natural state.

Adapting this approach could benefit Canadian cities and provinces in the short term. It may be possible that future technologies and practices will allow us to assign dollar values to specific natural properties, but this requires a consensus on monetizing aspects like soil carbon sequestration. That’s a long way off for a nation still struggling with a consumption tax on fuel carbon.

In the meantime, we must agree that urban green space is valuable and that developments encroaching on parklands will weaken the ability of natural systems to sustain themselves—and us. Valuation based on ecological integrity scores, rather than mere dollars and cents, provides a quantitative measure to assess the wisdom of the "improvements" agencies make to lands we own.

(Title photo from Evergreen)